I recently re-read a review I wrote on “Stuffed”, a book that critiques the roles industry and governments play in the obesity epidemic, and one that has come up a few times in discussions with my students recently. I’m sharing it, in an attempt to get myself back in the blogging habit. 😊 The references are a little outdated, but still stand (though, I will refresh them a bit over the next few days).

A food industry insider, Hank Cardello laments the role corporations play in expanding America’s collective girth. His book portrays consumers as being virtually helpless in the face of corporate marketing ploys and failed government attempts to make Americans healthier. While he excuses corporate behavior as being necessary in order to stay profitable, he admonishes the government for taking on a regulatory role. Cardello is self-admittedly against government regulation of the food industry, except in terms of overseeing food safety issues such as Mad Cow and E coli.

Beyond making sure our food is safe to eat, he sees no need for government to be involved in matters of nutrition.

With few exceptions, Cardello doesn’t tell us much that is surprising. He fills more than two thirds of his book with detailed descriptions of marketing ploys, advertising tricks (on the airways, in print, and in America’s stores and restaurants), and a running campaign against government control over virtually all things food industry related. Statistics are scarce, and when they do show up, they are generally presented with lightly veiled bias.

For instance, in an effort to place some of the blame on sugar consumption, Cardello cites these comparative statistics: “in the 1950s” he says, “kids drank three cups of milk for every cup of soda. Today, the ratio is reversed. Think of the overall impact: a typical 12-ounce can of soda is 10 percent sugar, or ten teaspoons. Three sodas are almost 450 calories of sugar. The typical American drinks a gallon of soda every week” (1).

Shocking indeed. That is, until we look more carefully at the details. First off, he equates drinking three cups of soda with three cans of the same. Second, one cup of milk in the 1950’s meant a cup of whole milk. According to the USDA nutrient database for standard reference, one cup of whole milk has 149 calories, 4.55 grams of saturated fat, and 13 grams of sugar (2). Thus,

3 cups of milk + 1 cup of soda = 597 calories, 62 grams of sugar, 13.65 grams of saturated fat

3 cups of soda + 1 one cup of milk = 599 calories, 82 grams of sugar, 4.55 grams of saturated fat

The difference in sugar content is overshadowed by the saturated fat content of whole milk.

A chapter dedicated to explaining how larger portions increase profits for retail and restaurant businesses is, perhaps, one of the book’s most interesting eye openers. Cardello explains: “If I make my muffins bigger, my ingredient costs go up, but not as much as the price I can charge. Therefore I make a higher profit with the larger size. Same holds for french fries. Same holds for beverages” (1). He points out that the same is true of combo meals. While a combo meal saves the consumer some money per item, the consumer often ends up purchasing more items than s/he would have otherwise, and, thus, s/he ends up spending more. After all, why buy just a burger and a drink when a combo is available that also includes fries, for just a dollar more?

All you can eat buffets operate much in the same way and are, perhaps, more dangerous in terms of calories consumed because, unlike a meal at a fast food or conventional restaurant, “doggie bags” are not part of the deal. The patron must consume all the food included in the seemingly reasonable price right on the spot. To eat any less leaves the consumer feeling s/he did not get “a deal”. Overeating, in such an environment, is almost inevitable.

Cardello’s anti-government bias permeates the pages of “Stuffed”. He points out errors in some government regulation attempts and concludes the government should play no role at all in helping Americans achieve healthier nutrition status as a result. This is illogical at best. Programs (government run or otherwise) that don’t work can be adjusted or replaced with programs that are beneficial. He states: “In the last fifty years, the failures of federal, state, and local governments in the United States to create a workable guidance and regulatory system have played an important role in making Americans fatter” (1). To support his opinion of government inadequacy, Cardello sometimes uses outrageous examples as if they are the law of the land: “The height of ludicrous government behavior perhaps revealed itself in Mississippi, when there was a proposal to refuse service to obese people in restaurants. Who’s going to be the arbiter of fat in the obviously panicky Magnolia State?” (1).

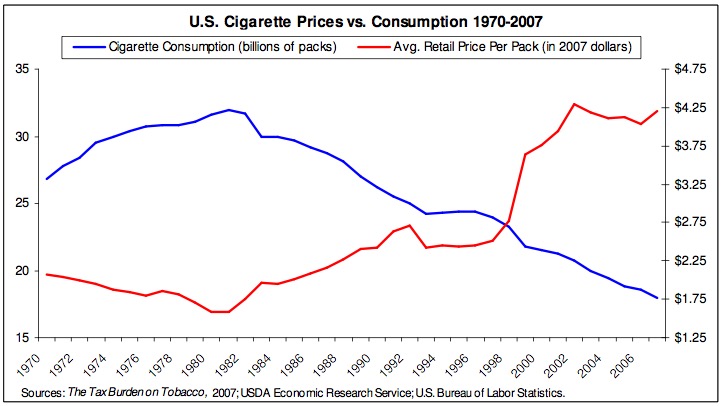

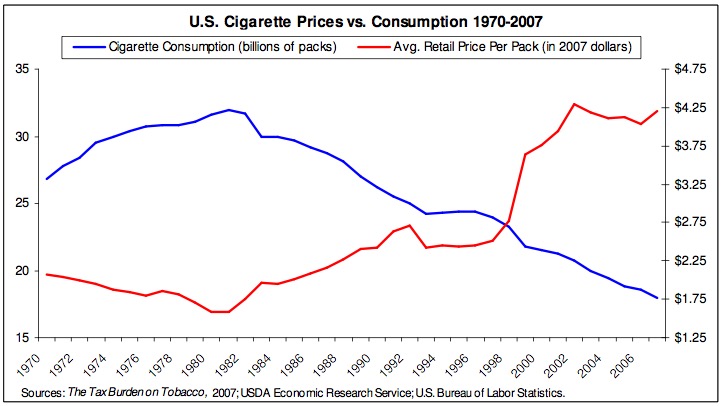

Taxation of empty calorie, artery clogging, fat laden foods is not something Cardello wants to see. He views the “sin tax” as being useless. But is it? When independent research surpassed that of the tobacco industry and showed the public once and for all that tobacco use significantly raises the risk of lung cancer, emphysema, and CVD, the government took notice. Since their implementation over a decade ago, the sin taxes on tobacco products have played an important role in significantly lowering consumption rates (3). As cigarette prices went up, consumption went down. This, of course, may be a coincidence, but the trend has continued to date.

<<<<<<<<

<<<<<<<<

g with this mindset, Cardello asks: “Have we witnessed any government programs and regulations that have proven to lower the rates of obesity in this country?”

Uhm… yes.

At the local level, programs overlooking school lunches in several communities have had great results (4). Five elementary schools in Osceola County, Florida, participated in a two year nutrition education program which integrated nutrition, physical activity, and lifestyle education curricula in an effort to help kids learn how to eat healthier foods and keep their weight in check. The results were significant, particularly in light of the fact that the school could only control food intake during lunch and snack time, having no control over what the kids would eat when off the school grounds. Blood pressure improved significantly and overall weight and body mass index improved considerably (5). This is one example of a public school program that, should it be implemented permanently, can have beneficial results.

Cardello provides some unexpected, and perhaps counterintuitive, solutions in his concluding chapters. Although he places the blame for America’s weight problems mainly on the food industry’s lack of concern for consumer health, Cardello insists that it is the industry itself that must fix the problem, not the government, and surely not the consumers.

He envisions a future when people can eat whatever they want and will not have to worry about calories, fat content, and climbing cholesterol levels. He sees GMOs, modified fats and artificial sweeteners as the answer to all of America’s weight problems.

While I share the author's enthusiasm for GMOs, I can't say the same for sweeteners and fats. Zero calorie drinks seem to be the author's favorite solution, in spite of questionable effects they may have in terms of longterm weight management. Recent research has shown that the body "keeps track" of nutrients and the calories they provide through the use of sensors along the GI tract. When repeatedly presented with a zero calorie beverage, which the body expects to have a caloric value (nothing in nature tastes sweet but has zero calories), over the longterm, the mechanism which keeps track of energy intake becomes “confused”, for lack of a better word. This disruption appears to negatively impacts appetite and weight regulation, though, more research is needed to identify the mechanism of action (7, 8).

Cardello admits that artificial replacements of problem foods can create more problems: "Among the frying oils fast replacing them is what’s known as interesterified (IE) oils. While devoid of trans fats, these new oils may help create a new demon. Recent research by K. C. Hayes, the noted expert on fats at Brandeis University, reported in Nutrition and Metabolism, that IE oils resulted in elevated fasting glucose levels and reduced insulin values compared with naturally structured fats. In fact, according to his study, they were even worse than the partially hydrogenated (high–trans fat) oils they replaced." (1) At the same time, he proposes these kinds of ingredients as the solution to America’s weight management problem. He calls their inclusion in the food supply without much fanfare “Stealth Health”.

Cardello may have lost all faith in the consumer, but, these days, people are paying more attention to ingredients and the quality of the foods they eat than ever before. The problem is they’re being duped by corporate advertising and the kinds of marketing tactics he describes.

Although an informative and entertaining read, Cardello’s “Stuffed” fizzles out in the end. His so-called solutions to the problem risk becoming problems themselves.

References

1. Cardello H. Stuffed: An Insider's Look at Who's (Really) Making America Fat. Ecco. 2009

2. USDA Agricultural Research Service Nutrient Data Laboratory http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/ Accessed on July 10, 2010.

3. Orzechowski, Walker. The Tax Burden. 2007

4. Belkin L. The school lunch test. New York Times. 2006, August 20.

5. Hollar D, Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Hollar TL, Almon M, Agatston AS. Healthier options for public schoolchildren program improves weight and blood pressure in 6- to 13-year-olds. University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010; 110(2):261-7.

6. Biing-Hwan L. Healthy Eating Index, USDA Economic Research Service, Agriculture Information Bulletin Number 796-3, U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2005

7. Swithers SE, Davidson TL. A Role for Sweet Taste: Calorie Predictive Relations in Energy Regulation by Rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008; 122: 1

8. Fowler SP. Abstract 1058-P presented at the 65th Annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Diego. 2005, June 10-14.

<<<<<<<<

<<<<<<<<